To understand the programming model, you should be familiar with the following core concepts:

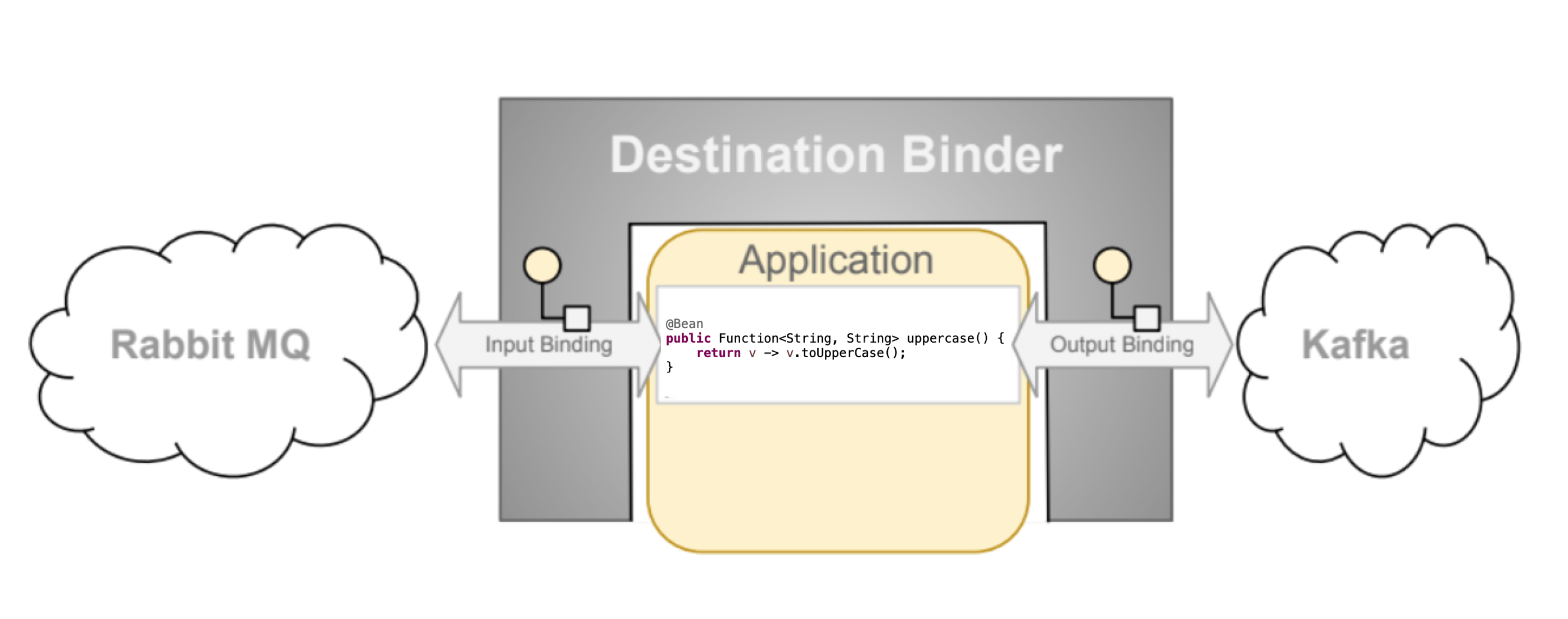

- Destination Binders: Components responsible to provide integration with the external messaging systems.

- Destination Bindings: Bridge between the external messaging systems and application provided Producers and Consumers of messages (created by the Destination Binders).

- Message: The canonical data structure used by producers and consumers to communicate with Destination Binders (and thus other applications via external messaging systems).

Destination Binders are extension components of Spring Cloud Stream responsible for providing the necessary configuration and implementation to facilitate integration with external messaging systems. This integration is responsible for connectivity, delegation, and routing of messages to and from producers and consumers, data type conversion, invocation of the user code, and more.

Binders handle a lot of the boiler plate responsibilities that would otherwise fall on your shoulders. However, to accomplish that, the binder still needs some help in the form of minimalistic yet required set of instructions from the user, which typically come in the form of some type of configuration.

While it is out of scope of this section to discuss all of the available binder and binding configuration options (the rest of the manual covers them extensively), Destination Binding does require special attention. The next section discusses it in detail.

As stated earlier, Destination Bindings provide a bridge between the external messaging system and application-provided Producers and Consumers.

Applying the @EnableBinding annotation to one of the application’s configuration classes defines a destination binding.

The @EnableBinding annotation itself is meta-annotated with @Configuration and triggers the configuration of the Spring Cloud Stream infrastructure.

The following example shows a fully configured and functioning Spring Cloud Stream application that receives the payload of the message from the INPUT

destination as a String type (see Chapter 9, Content Type Negotiation section), logs it to the console and sends it to the OUTPUT destination after converting it to upper case.

@SpringBootApplication @EnableBinding(Processor.class) public class MyApplication { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication.run(MyApplication.class, args); } @StreamListener(Processor.INPUT) @SendTo(Processor.OUTPUT) public String handle(String value) { System.out.println("Received: " + value); return value.toUpperCase(); } }

As you can see the @EnableBinding annotation can take one or more interface classes as parameters. The parameters are referred to as bindings,

and they contain methods representing bindable components.

These components are typically message channels (see Spring Messaging)

for channel-based binders (such as Rabbit, Kafka, and others). However other types of bindings can

provide support for the native features of the corresponding technology. For example Kafka Streams binder (formerly known as KStream) allows native bindings directly to Kafka Streams

(see Kafka Streams for more details).

Spring Cloud Stream already provides binding interfaces for typical message exchange contracts, which include:

- Sink: Identifies the contract for the message consumer by providing the destination from which the message is consumed.

- Source: Identifies the contract for the message producer by providing the destination to which the produced message is sent.

- Processor: Encapsulates both the sink and the source contracts by exposing two destinations that allow consumption and production of messages.

public interface Sink { String INPUT = "input"; @Input(Sink.INPUT) SubscribableChannel input(); }

public interface Source { String OUTPUT = "output"; @Output(Source.OUTPUT) MessageChannel output(); }

public interface Processor extends Source, Sink {}

While the preceding example satisfies the majority of cases, you can also define your own contracts by defining your own bindings interfaces and use @Input and @Output

annotations to identify the actual bindable components.

For example:

public interface Barista { @Input SubscribableChannel orders(); @Output MessageChannel hotDrinks(); @Output MessageChannel coldDrinks(); }

Using the interface shown in the preceding example as a parameter to @EnableBinding triggers the creation of the three bound channels named orders, hotDrinks, and coldDrinks,

respectively.

You can provide as many binding interfaces as you need, as arguments to the @EnableBinding annotation, as shown in the following example:

@EnableBinding(value = { Orders.class, Payment.class })In Spring Cloud Stream, the bindable MessageChannel components are the Spring Messaging MessageChannel (for outbound) and its extension, SubscribableChannel,

(for inbound).

Pollable Destination Binding

While the previously described bindings support event-based message consumption, sometimes you need more control, such as rate of consumption.

Starting with version 2.0, you can now bind a pollable consumer:

The following example shows how to bind a pollable consumer:

public interface PolledBarista { @Input PollableMessageSource orders(); . . . }

In this case, an implementation of PollableMessageSource is bound to the orders “channel”. See Section 6.3.5, “Using Polled Consumers” for more details.

Customizing Channel Names

By using the @Input and @Output annotations, you can specify a customized channel name for the channel, as shown in the following example:

public interface Barista { @Input("inboundOrders") SubscribableChannel orders(); }

In the preceding example, the created bound channel is named inboundOrders.

Normally, you need not access individual channels or bindings directly (other then configuring them via @EnableBinding annotation). However there may be

times, such as testing or other corner cases, when you do.

Aside from generating channels for each binding and registering them as Spring beans, for each bound interface, Spring Cloud Stream generates a bean that implements the interface. That means you can have access to the interfaces representing the bindings or individual channels by auto-wiring either in your application, as shown in the following two examples:

Autowire Binding interface

@Autowire private Source source public void sayHello(String name) { source.output().send(MessageBuilder.withPayload(name).build()); }

Autowire individual channel

@Autowire private MessageChannel output; public void sayHello(String name) { output.send(MessageBuilder.withPayload(name).build()); }

You can also use standard Spring’s @Qualifier annotation for cases when channel names are customized or in multiple-channel scenarios that require specifically named channels.

The following example shows how to use the @Qualifier annotation in this way:

@Autowire @Qualifier("myChannel") private MessageChannel output;

You can write a Spring Cloud Stream application by using either Spring Integration annotations or Spring Cloud Stream native annotation.

Spring Cloud Stream is built on the concepts and patterns defined by Enterprise Integration Patterns and relies in its internal implementation on an already established and popular implementation of Enterprise Integration Patterns within the Spring portfolio of projects: Spring Integration framework.

So its only natural for it to support the foundation, semantics, and configuration options that are already established by Spring Integration

For example, you can attach the output channel of a Source to a MessageSource and use the familiar @InboundChannelAdapter annotation, as follows:

@EnableBinding(Source.class) public class TimerSource { @Bean @InboundChannelAdapter(value = Source.OUTPUT, poller = @Poller(fixedDelay = "10", maxMessagesPerPoll = "1")) public MessageSource<String> timerMessageSource() { return () -> new GenericMessage<>("Hello Spring Cloud Stream"); } }

Similarly, you can use @Transformer or @ServiceActivator while providing an implementation of a message handler method for a Processor binding contract, as shown in the following example:

@EnableBinding(Processor.class) public class TransformProcessor { @Transformer(inputChannel = Processor.INPUT, outputChannel = Processor.OUTPUT) public Object transform(String message) { return message.toUpperCase(); } }

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

While this may be skipping ahead a bit, it is important to understand that, when you consume from the same binding using |

Complementary to its Spring Integration support, Spring Cloud Stream provides its own @StreamListener annotation, modeled after other Spring Messaging annotations

(@MessageMapping, @JmsListener, @RabbitListener, and others) and provides conviniences, such as content-based routing and others.

@EnableBinding(Sink.class) public class VoteHandler { @Autowired VotingService votingService; @StreamListener(Sink.INPUT) public void handle(Vote vote) { votingService.record(vote); } }

As with other Spring Messaging methods, method arguments can be annotated with @Payload, @Headers, and @Header.

For methods that return data, you must use the @SendTo annotation to specify the output binding destination for data returned by the method, as shown in the following example:

@EnableBinding(Processor.class) public class TransformProcessor { @Autowired VotingService votingService; @StreamListener(Processor.INPUT) @SendTo(Processor.OUTPUT) public VoteResult handle(Vote vote) { return votingService.record(vote); } }

Spring Cloud Stream supports dispatching messages to multiple handler methods annotated with @StreamListener based on conditions.

In order to be eligible to support conditional dispatching, a method must satisfy the follow conditions:

- It must not return a value.

- It must be an individual message handling method (reactive API methods are not supported).

The condition is specified by a SpEL expression in the condition argument of the annotation and is evaluated for each message.

All the handlers that match the condition are invoked in the same thread, and no assumption must be made about the order in which the invocations take place.

In the following example of a @StreamListener with dispatching conditions, all the messages bearing a header type with the value bogey are dispatched to the

receiveBogey method, and all the messages bearing a header type with the value bacall are dispatched to the receiveBacall method.

@EnableBinding(Sink.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class TestPojoWithAnnotatedArguments { @StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "headers['type']=='bogey'") public void receiveBogey(@Payload BogeyPojo bogeyPojo) { // handle the message } @StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "headers['type']=='bacall'") public void receiveBacall(@Payload BacallPojo bacallPojo) { // handle the message } }

Content Type Negotiation in the Context of condition

It is important to understand some of the mechanics behind content-based routing using the condition argument of @StreamListener, especially in the context of the type of the message as a whole.

It may also help if you familiarize yourself with the Chapter 9, Content Type Negotiation before you proceed.

Consider the following scenario:

@EnableBinding(Sink.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class CatsAndDogs { @StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "payload.class.simpleName=='Dog'") public void bark(Dog dog) { // handle the message } @StreamListener(target = Sink.INPUT, condition = "payload.class.simpleName=='Cat'") public void purr(Cat cat) { // handle the message } }

The preceding code is perfectly valid. It compiles and deploys without any issues, yet it never produces the result you expect.

That is because you are testing something that does not yet exist in a state you expect. That is because the payload of the message is not yet converted from the

wire format (byte[]) to the desired type.

In other words, it has not yet gone through the type conversion process described in the Chapter 9, Content Type Negotiation.

So, unless you use a SPeL expression that evaluates raw data (for example, the value of the first byte in the byte array), use message header-based expressions

(such as condition = "headers['type']=='dog'").

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

At the moment, dispatching through |

Since Spring Cloud Stream v2.1, another alternative for defining stream handlers and sources is to use build-in

support for Spring Cloud Function where they can be expressed as beans of

type java.util.function.[Supplier/Function/Consumer].

To specify which functional bean to bind to the external destination(s) exposed by the bindings, you must provide spring.cloud.stream.function.definition property.

Here is the example of the Processor application exposing message handler as java.util.function.Function

@SpringBootApplication @EnableBinding(Processor.class) public class MyFunctionBootApp { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication.run(MyFunctionBootApp.class, "--spring.cloud.stream.function.definition=toUpperCase"); } @Bean public Function<String, String> toUpperCase() { return s -> s.toUpperCase(); } }

In the above you we simply define a bean of type java.util.function.Function called toUpperCase and identify it as a bean to be used as message handler

whose 'input' and 'output' must be bound to the external destinations exposed by the Processor binding.

Below are the examples of simple functional applications to support Source, Processor and Sink.

Here is the example of a Source application defined as java.util.function.Supplier

@SpringBootApplication @EnableBinding(Source.class) public static class SourceFromSupplier { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication.run(SourceFromSupplier.class, "--spring.cloud.stream.function.definition=date"); } @Bean public Supplier<Date> date() { return () -> new Date(12345L); } }

Here is the example of a Processor application defined as java.util.function.Function

@SpringBootApplication @EnableBinding(Processor.class) public static class ProcessorFromFunction { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication.run(ProcessorFromFunction.class, "--spring.cloud.stream.function.definition=toUpperCase"); } @Bean public Function<String, String> toUpperCase() { return s -> s.toUpperCase(); } }

Here is the example of a Sink application defined as java.util.function.Consumer

@EnableAutoConfiguration @EnableBinding(Sink.class) public static class SinkFromConsumer { public static void main(String[] args) { SpringApplication.run(SinkFromConsumer.class, "--spring.cloud.stream.function.definition=sink"); } @Bean public Consumer<String> sink() { return System.out::println; } }

Using this programming model you can also benefit from functional composition where you can dynamically compose complex handlers from a set of simple functions. As an example let’s add the following function bean to the application defined above

@Bean public Function<String, String> wrapInQuotes() { return s -> "\"" + s + "\""; }

and modify the spring.cloud.stream.function.definition property to reflect your intention to compose a new function from both ‘toUpperCase’ and ‘wrapInQuotes’.

To do that Spring Cloud Function allows you to use | (pipe) symbol. So to finish our example our property will now look like this:

—spring.cloud.stream.function.definition=toUpperCase|wrapInQuotes

When using polled consumers, you poll the PollableMessageSource on demand.

Consider the following example of a polled consumer:

public interface PolledConsumer { @Input PollableMessageSource destIn(); @Output MessageChannel destOut(); }

Given the polled consumer in the preceding example, you might use it as follows:

@Bean public ApplicationRunner poller(PollableMessageSource destIn, MessageChannel destOut) { return args -> { while (someCondition()) { try { if (!destIn.poll(m -> { String newPayload = ((String) m.getPayload()).toUpperCase(); destOut.send(new GenericMessage<>(newPayload)); })) { Thread.sleep(1000); } } catch (Exception e) { // handle failure } } }; }

The PollableMessageSource.poll() method takes a MessageHandler argument (often a lambda expression, as shown here).

It returns true if the message was received and successfully processed.

As with message-driven consumers, if the MessageHandler throws an exception, messages are published to error channels,

as discussed in Section 6.4, “Error Handling”.

Normally, the poll() method acknowledges the message when the MessageHandler exits.

If the method exits abnormally, the message is rejected (not re-queued), but see the section called “Handling Errors”.

You can override that behavior by taking responsibility for the acknowledgment, as shown in the following example:

@Bean public ApplicationRunner poller(PollableMessageSource dest1In, MessageChannel dest2Out) { return args -> { while (someCondition()) { if (!dest1In.poll(m -> { StaticMessageHeaderAccessor.getAcknowledgmentCallback(m).noAutoAck(); // e.g. hand off to another thread which can perform the ack // or acknowledge(Status.REQUEUE) })) { Thread.sleep(1000); } } }; }

![[Important]](images/important.png) | Important |

|---|---|

You must |

![[Important]](images/important.png) | Important |

|---|---|

Some messaging systems (such as Apache Kafka) maintain a simple offset in a log. If a delivery fails and is re-queued with |

There is also an overloaded poll method, for which the definition is as follows:

poll(MessageHandler handler, ParameterizedTypeReference<?> type)

The type is a conversion hint that allows the incoming message payload to be converted, as shown in the following example:

boolean result = pollableSource.poll(received -> { Map<String, Foo> payload = (Map<String, Foo>) received.getPayload(); ... }, new ParameterizedTypeReference<Map<String, Foo>>() {});

By default, an error channel is configured for the pollable source; if the callback throws an exception, an ErrorMessage is sent to the error channel (<destination>.<group>.errors); this error channel is also bridged to the global Spring Integration errorChannel.

You can subscribe to either error channel with a @ServiceActivator to handle errors; without a subscription, the error will simply be logged and the message will be acknowledged as successful.

If the error channel service activator throws an exception, the message will be rejected (by default) and won’t be redelivered.

If the service activator throws a RequeueCurrentMessageException, the message will be requeued at the broker and will be again retrieved on a subsequent poll.

If the listener throws a RequeueCurrentMessageException directly, the message will be requeued, as discussed above, and will not be sent to the error channels.

Errors happen, and Spring Cloud Stream provides several flexible mechanisms to handle them. The error handling comes in two flavors:

- application: The error handling is done within the application (custom error handler).

- system: The error handling is delegated to the binder (re-queue, DL, and others). Note that the techniques are dependent on binder implementation and the capability of the underlying messaging middleware.

Spring Cloud Stream uses the Spring Retry library to facilitate successful message processing. See Section 6.4.3, “Retry Template” for more details. However, when all fails, the exceptions thrown by the message handlers are propagated back to the binder. At that point, binder invokes custom error handler or communicates the error back to the messaging system (re-queue, DLQ, and others).

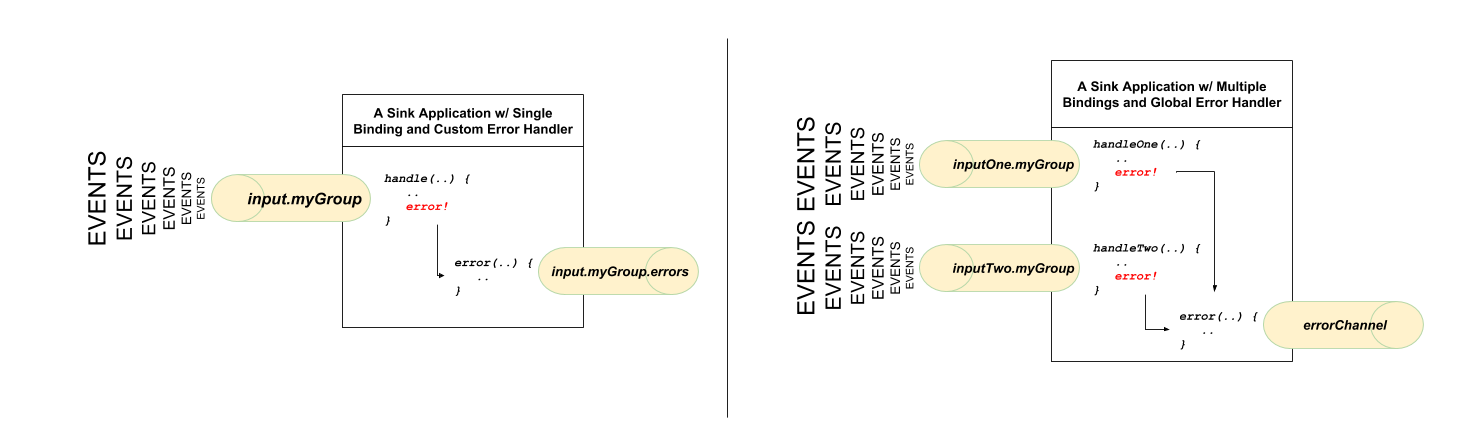

There are two types of application-level error handling. Errors can be handled at each binding subscription or a global handler can handle all the binding subscription errors. Let’s review the details.

For each input binding, Spring Cloud Stream creates a dedicated error channel with the following semantics <destinationName>.errors.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

The |

Consider the following:

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.group=myGroup

@StreamListener(Sink.INPUT) // destination name 'input.myGroup' public void handle(Person value) { throw new RuntimeException("BOOM!"); } @ServiceActivator(inputChannel = Processor.INPUT + ".myGroup.errors") //channel name 'input.myGroup.errors' public void error(Message<?> message) { System.out.println("Handling ERROR: " + message); }

In the preceding example the destination name is input.myGroup and the dedicated error channel name is input.myGroup.errors.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

The use of @StreamListener annotation is intended specifically to define bindings that bridge internal channels and external destinations. Given that the destination specific error channel does NOT have an associated external destination, such channel is a prerogative of Spring Integration (SI). This means that the handler for such destination must be defined using one of the SI handler annotations (i.e., @ServiceActivator, @Transformer etc.). |

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

If |

Also, in the event you are binding to the existing destination such as:

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.destination=myFooDestination spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.group=myGroup

the full destination name is myFooDestination.myGroup and then the dedicated error channel name is myFooDestination.myGroup.errors.

Back to the example…

The handle(..) method, which subscribes to the channel named input, throws an exception. Given there is also a subscriber to the error channel input.myGroup.errors

all error messages are handled by this subscriber.

If you have multiple bindings, you may want to have a single error handler. Spring Cloud Stream automatically provides support for

a global error channel by bridging each individual error channel to the channel named errorChannel, allowing a single subscriber to handle all errors,

as shown in the following example:

@StreamListener("errorChannel") public void error(Message<?> message) { System.out.println("Handling ERROR: " + message); }

This may be a convenient option if error handling logic is the same regardless of which handler produced the error.

System-level error handling implies that the errors are communicated back to the messaging system and, given that not every messaging system is the same, the capabilities may differ from binder to binder.

That said, in this section we explain the general idea behind system level error handling and use Rabbit binder as an example. NOTE: Kafka binder provides similar support, although some configuration properties do differ. Also, for more details and configuration options, see the individual binder’s documentation.

If no internal error handlers are configured, the errors propagate to the binders, and the binders subsequently propagate those errors back to the messaging system. Depending on the capabilities of the messaging system such a system may drop the message, re-queue the message for re-processing or send the failed message to DLQ. Both Rabbit and Kafka support these concepts. However, other binders may not, so refer to your individual binder’s documentation for details on supported system-level error-handling options.

By default, if no additional system-level configuration is provided, the messaging system drops the failed message. While acceptable in some cases, for most cases, it is not, and we need some recovery mechanism to avoid message loss.

DLQ allows failed messages to be sent to a special destination: - Dead Letter Queue.

When configured, failed messages are sent to this destination for subsequent re-processing or auditing and reconciliation.

For example, continuing on the previous example and to set up the DLQ with Rabbit binder, you need to set the following property:

spring.cloud.stream.rabbit.bindings.input.consumer.auto-bind-dlq=true

Keep in mind that, in the above property, input corresponds to the name of the input destination binding.

The consumer indicates that it is a consumer property and auto-bind-dlq instructs the binder to configure DLQ for input

destination, which results in an additional Rabbit queue named input.myGroup.dlq.

Once configured, all failed messages are routed to this queue with an error message similar to the following:

delivery_mode: 1

headers:

x-death:

count: 1

reason: rejected

queue: input.hello

time: 1522328151

exchange:

routing-keys: input.myGroup

Payload {"name”:"Bob"}As you can see from the above, your original message is preserved for further actions.

However, one thing you may have noticed is that there is limited information on the original issue with the message processing. For example, you do not see a stack trace corresponding to the original error. To get more relevant information about the original error, you must set an additional property:

spring.cloud.stream.rabbit.bindings.input.consumer.republish-to-dlq=true

Doing so forces the internal error handler to intercept the error message and add additional information to it before publishing it to DLQ. Once configured, you can see that the error message contains more information relevant to the original error, as follows:

delivery_mode: 2

headers:

x-original-exchange:

x-exception-message: has an error

x-original-routingKey: input.myGroup

x-exception-stacktrace: org.springframework.messaging.MessageHandlingException: nested exception is

org.springframework.messaging.MessagingException: has an error, failedMessage=GenericMessage [payload=byte[15],

headers={amqp_receivedDeliveryMode=NON_PERSISTENT, amqp_receivedRoutingKey=input.hello, amqp_deliveryTag=1,

deliveryAttempt=3, amqp_consumerQueue=input.hello, amqp_redelivered=false, id=a15231e6-3f80-677b-5ad7-d4b1e61e486e,

amqp_consumerTag=amq.ctag-skBFapilvtZhDsn0k3ZmQg, contentType=application/json, timestamp=1522327846136}]

at org.spring...integ...han...MethodInvokingMessageProcessor.processMessage(MethodInvokingMessageProcessor.java:107)

at. . . . .

Payload {"name”:"Bob"}This effectively combines application-level and system-level error handling to further assist with downstream troubleshooting mechanics.

As mentioned earlier, the currently supported binders (Rabbit and Kafka) rely on RetryTemplate to facilitate successful message processing. See Section 6.4.3, “Retry Template” for details.

However, for cases when max-attempts property is set to 1, internal reprocessing of the message is disabled. At this point, you can facilitate message re-processing (re-tries)

by instructing the messaging system to re-queue the failed message. Once re-queued, the failed message is sent back to the original handler, essentially creating a retry loop.

This option may be feasible for cases where the nature of the error is related to some sporadic yet short-term unavailability of some resource.

To accomplish that, you must set the following properties:

spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.consumer.max-attempts=1 spring.cloud.stream.rabbit.bindings.input.consumer.requeue-rejected=true

In the preceding example, the max-attempts set to 1 essentially disabling internal re-tries and requeue-rejected (short for requeue rejected messages) is set to true.

Once set, the failed message is resubmitted to the same handler and loops continuously or until the handler throws AmqpRejectAndDontRequeueException

essentially allowing you to build your own re-try logic within the handler itself.

The RetryTemplate is part of the Spring Retry library.

While it is out of scope of this document to cover all of the capabilities of the RetryTemplate, we will mention the following consumer properties that are specifically related to

the RetryTemplate:

- maxAttempts

The number of attempts to process the message.

Default: 3.

- backOffInitialInterval

The backoff initial interval on retry.

Default 1000 milliseconds.

- backOffMaxInterval

The maximum backoff interval.

Default 10000 milliseconds.

- backOffMultiplier

The backoff multiplier.

Default 2.0.

- defaultRetryable

Whether exceptions thrown by the listener that are not listed in the

retryableExceptionsare retryable.Default:

true.- retryableExceptions

A map of Throwable class names in the key and a boolean in the value. Specify those exceptions (and subclasses) that will or won’t be retried. Also see

defaultRetriable. Example:spring.cloud.stream.bindings.input.consumer.retryable-exceptions.java.lang.IllegalStateException=false.Default: empty.

While the preceding settings are sufficient for majority of the customization requirements, they may not satisfy certain complex requirements at, which

point you may want to provide your own instance of the RetryTemplate. To do so configure it as a bean in your application configuration. The application provided

instance will override the one provided by the framework. Also, to avoid conflicts you must qualify the instance of the RetryTemplate you want to be used by the binder

as @StreamRetryTemplate. For example,

@StreamRetryTemplate public RetryTemplate myRetryTemplate() { return new RetryTemplate(); }

As you can see from the above example you don’t need to annotate it with @Bean since @StreamRetryTemplate is a qualified @Bean.

Spring Cloud Stream also supports the use of reactive APIs where incoming and outgoing data is handled as continuous data flows.

Support for reactive APIs is available through spring-cloud-stream-reactive, which needs to be added explicitly to your project.

The programming model with reactive APIs is declarative. Instead of specifying how each individual message should be handled, you can use operators that describe functional transformations from inbound to outbound data flows.

At present Spring Cloud Stream supports the only the Reactor API. In the future, we intend to support a more generic model based on Reactive Streams.

The reactive programming model also uses the @StreamListener annotation for setting up reactive handlers.

The differences are that:

- The

@StreamListenerannotation must not specify an input or output, as they are provided as arguments and return values from the method. - The arguments of the method must be annotated with

@Inputand@Output, indicating which input or output the incoming and outgoing data flows connect to, respectively. - The return value of the method, if any, is annotated with

@Output, indicating the input where data should be sent.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

Reactive programming support requires Java 1.8. |

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

As of Spring Cloud Stream 1.1.1 and later (starting with release train Brooklyn.SR2), reactive programming support requires the use of Reactor 3.0.4.RELEASE and higher.

Earlier Reactor versions (including 3.0.1.RELEASE, 3.0.2.RELEASE and 3.0.3.RELEASE) are not supported.

|

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|---|

The use of term, “reactive”, currently refers to the reactive APIs being used and not to the execution model being reactive (that is, the bound endpoints still use a 'push' rather than a 'pull' model). While some backpressure support is provided by the use of Reactor, we do intend, in a future release, to support entirely reactive pipelines by the use of native reactive clients for the connected middleware. |

A Reactor-based handler can have the following argument types:

- For arguments annotated with

@Input, it supports the ReactorFluxtype. The parameterization of the inbound Flux follows the same rules as in the case of individual message handling: It can be the entireMessage, a POJO that can be theMessagepayload, or a POJO that is the result of a transformation based on theMessagecontent-type header. Multiple inputs are provided. - For arguments annotated with

Output, it supports theFluxSendertype, which connects aFluxproduced by the method with an output. Generally speaking, specifying outputs as arguments is only recommended when the method can have multiple outputs.

A Reactor-based handler supports a return type of Flux. In that case, it must be annotated with @Output. We recommend using the return value of the method when a single output Flux is available.

The following example shows a Reactor-based Processor:

@EnableBinding(Processor.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class UppercaseTransformer { @StreamListener @Output(Processor.OUTPUT) public Flux<String> receive(@Input(Processor.INPUT) Flux<String> input) { return input.map(s -> s.toUpperCase()); } }

The same processor using output arguments looks like the following example:

@EnableBinding(Processor.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class UppercaseTransformer { @StreamListener public void receive(@Input(Processor.INPUT) Flux<String> input, @Output(Processor.OUTPUT) FluxSender output) { output.send(input.map(s -> s.toUpperCase())); } }

Spring Cloud Stream reactive support also provides the ability for creating reactive sources through the @StreamEmitter annotation.

By using the @StreamEmitter annotation, a regular source may be converted to a reactive one.

@StreamEmitter is a method level annotation that marks a method to be an emitter to outputs declared with @EnableBinding.

You cannot use the @Input annotation along with @StreamEmitter, as the methods marked with this annotation are not listening for any input. Rather, methods marked with @StreamEmitter generate output.

Following the same programming model used in @StreamListener, @StreamEmitter also allows flexible ways of using the @Output annotation, depending on whether the method has any arguments, a return type, and other considerations.

The remainder of this section contains examples of using the @StreamEmitter annotation in various styles.

The following example emits the Hello, World message every millisecond and publishes to a Reactor Flux:

@EnableBinding(Source.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class HelloWorldEmitter { @StreamEmitter @Output(Source.OUTPUT) public Flux<String> emit() { return Flux.intervalMillis(1) .map(l -> "Hello World"); } }

In the preceding example, the resulting messages in the Flux are sent to the output channel of the Source.

The next example is another flavor of an @StreamEmmitter that sends a Reactor Flux.

Instead of returning a Flux, the following method uses a FluxSender to programmatically send a Flux from a source:

@EnableBinding(Source.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class HelloWorldEmitter { @StreamEmitter @Output(Source.OUTPUT) public void emit(FluxSender output) { output.send(Flux.intervalMillis(1) .map(l -> "Hello World")); } }

The next example is exactly same as the above snippet in functionality and style.

However, instead of using an explicit @Output annotation on the method, it uses the annotation on the method parameter.

@EnableBinding(Source.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class HelloWorldEmitter { @StreamEmitter public void emit(@Output(Source.OUTPUT) FluxSender output) { output.send(Flux.intervalMillis(1) .map(l -> "Hello World")); } }

The last example in this section is yet another flavor of writing reacting sources by using the Reactive Streams Publisher API and taking advantage of the support for it in Spring Integration Java DSL.

The Publisher in the following example still uses Reactor Flux under the hood, but, from an application perspective, that is transparent to the user and only needs Reactive Streams and Java DSL for Spring Integration:

@EnableBinding(Source.class) @EnableAutoConfiguration public static class HelloWorldEmitter { @StreamEmitter @Output(Source.OUTPUT) @Bean public Publisher<Message<String>> emit() { return IntegrationFlows.from(() -> new GenericMessage<>("Hello World"), e -> e.poller(p -> p.fixedDelay(1))) .toReactivePublisher(); } }